Several years go, after participating in several cohorts of Powerful Learning Practices with Sheryl Nussbaum Beach and Will Richardson and with the support of another fantastic mentor in Robin Ellis, I realized that I had a lot of unlearning to do. One of the most challenging shifts for me to grapple with was to acknowledge that I was entirely too focused on what I was doing as a teacher and not enough on my students learning. What makes this so difficult for us as educators is that this attitude or mindset often leaves us in an uncomfortable state of tension. That tension exists because of what we think we know to be true about teaching and what the reality of learning is for students. We know that teachers have a tremendous impact on student learning, but it's not necessarily in ways that we traditionally think.

As educators, we face a generation of students who appear to be disengaged, unmotivated, and unwilling to learn in school. Yet, this is also a generation with more access to information, an immense will to connect with one another and the world beyond them, and an intrinsic desire to be creative and innovative. Our students are learning. It's just that they are doing it outside of school, without us. Certainly there is argument on both sides of the debate as to whether this type of less structured, self driven learning will actually produce a generation of "well-educated" Americans (as if anyone has EVER defined that well). Want evidence, just google the MOOC debate occurring in higher ed.

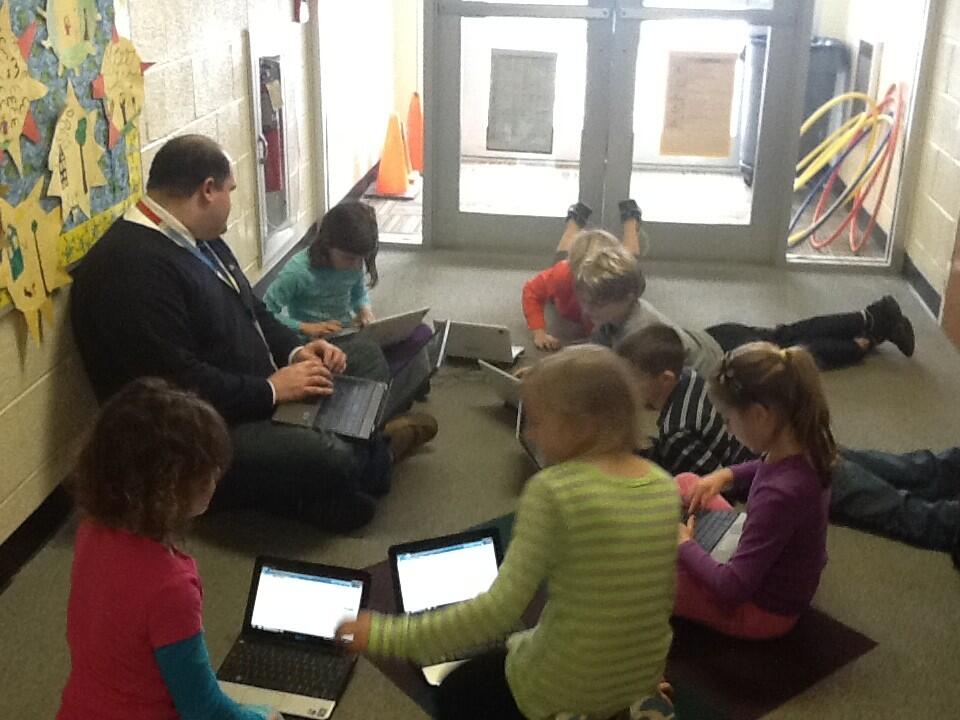

What has also become glaringly obvious to me is that many schools and classrooms rarely include students in the decision making process. And I'm not referring to a Student Government or Student Advisory Council which are both fantastic opportunities for students to have a voice. How often do we ask students how they want to learn? How often do we ask students what they would like to create? How often do we involve students in the design process? How often to do we ask them to co-create rubrics or determine what success looks like in THEIR growth and learning?

As a history teacher, I love to tell stories. It's inherent in what I do and it's part of my instructional toolbelt. We know that storytelling is paramount to understanding the past and making connections to modern life, yet if the same person is always telling the story (ie. the teacher) there is little learning that is occurring. Perhaps the kids are being passively entertained. Maybe the kids are being politely compliant. But if they aren't the ones telling the story, there is a limited chance that they will retain the story, let alone apply it or construct meaning from it.

In the debate over what it means to be "career and college ready" (as defined by CCSS) most educators can agree that one of the goals is to help support successful self-directed learning and learners. Yet somehow we seem to be missing a voice, a story: the students. As educators, we know a thing or two about content and pedagogy. We attempt to marry the art of teaching with the science of teaching. We utilize the brain based research equally with what our own guts tell us. Yet despite all of our training and experience, learning is magic(al) and mysterious. The only way to change that is to give control of learning over to the stakeholders themselves: the students.

If we continue to make every decision for our students about what to learn, how to learn it, and when to do it, we can not call them disengaged, or lazy, or incapable of achievement. If we control every part of their school day, their lack of engagement, their lack of effort, their lack of learning is actually a reflection on us. No matter what one-size fits all strategy we employ, no matter what "traditional" teaching methods we cling to, no matter what new innovative technologies we believe will transform our classrooms, if our students do not have control over their own learning journey's, we are failing them.